Inter-Agency Contingency Planning

Contingency plans (CPs) should be developed for identified moderate or high risks, including predictable seasonal hazards i.e. slow onset disasters (drought) and sudden disasters (cyclone, flood) as well as less predictable evolving hazards, such as conflict and mass movements. An inter-agency CP sets out the initial response strategy and operational plan (identifying resources) to meet the humanitarian needs during the immediate period of an emergency. Based on country specific requirements, it can be useful to plan for a longer period given the nature of, for example, agricultural assistance. If an emergency occurs, the CP will help inform a Flash Appeal as both follow the same format, approach and structure. See the IASC recommended ERP Contingency Plan Template (annex 7). The Flash Appeal is described in 9.5.1.

The FSC Coordinator should contribute to cluster specific inputs to the joint inter-agency CP covering:

- What could happen and what might be needed;

- Actions to take and resources required; and

- Gaps to be bridged.

FSC Specific Contingency Planning

If there is no inter-agency CP, the FSC should develop its own to cover the specific identified risks in a country. A cluster specific CP could either be requested by the HCT, CLAs, or decided by the FSC members / team. It should follow the IASC template (annex 7), which can be adapted for each disaster event. The FSC CP should provide a concise overview of the current food security situation in the country, and should be developed in such a way that it 1) can be rapidly and effectively transformed into a response plan when emergency strikes; and 2) it can inform resource mobilisation to ensure an appropriate response.

The CP process includes, at a minimum, the following activities:

- Identify the country risks and anticipate potential crisis:

- Analyse the likeliness of each identified risk happening (unless specific to the FSC, the risk information should be based on that agreed to at HCT (UNCT) level).

- Analyse the potential impact and consequences of each identified risk (severity).

- Build priority scenarios on the basis of likeliness and severity.

- Establish clear objectives, strategies and Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) to respond to each (or the most likely) scenario along with projected resource requirements whether human, financial or logistical and other actions to be taken to bridge gaps according to each scenario.

- Identify priority early actions (see early action and anticipatory actions below) required to strengthen the cluster’s readiness and mitigate the impact of the anticipated risk.

Although the document should be practical and easy to use in an emergency situation, having a higher level of details will improve the quality of the preparedness and response actions identified.

FSC Contingency Planning

- Example of FSC Contingency Planning: The FSC in Bangladesh developed two event-specific contingency plans (focused on cyclones and flood) in 2014. The FSC initiated the CP process alone (ahead of an inter-agency CP exercise). The process of developing the CPs was found to be as important as the final documents, ensuring partner buy-in and investment. Generic parts of the CP were developed by the FSC Coordinator (with CLA support) with a TWG preparing specific technical sections and both CPs were validated during FSC meetings. The food package was finalised jointly with the nutrition cluster and the CPs aligned with the Standing Order on Disaster (SOD) of the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief, and field workshops on how to operationalize the CPs included local level national authorities. The CPs included a short (“ABC Guidelines”) pocket version for field staff to carry. Find the Cyclone CP here and the Flood CP here. Each CP includes annexes such as MPAs, SOPs etc.

- Other examples: See Cluster Contingency Plan and MIRA Questionnaires and Food Security (Plan de contingence du cluster et Questionnaires MIRA et sécurité alimentaire - 2020) from Chad. Contact the GST for further examples.

Contingency Planning Good Practice:

- Contingency plans should be reviewed and updated on a regular basis. It should be included in the FSC workplan. During updates, consider demographic information such as population/area, ensure alignment with national CP processes, contingency stocks and ensure complementarity, up-to-date contact information at national, sub-national level, and district level, as well as resource requirements. Consider handy pocket sized laminated versions in English (or French/Spanish) and local language spoken and share widely.

- Periodic table-top exercises and simulations are recommended to ensure a high level of understanding and preparedness – especially ahead of seasonal weather patterns (cyclones, floods, drought). For an example of FSC emergency preparedness training with cluster partners, see here (Day 1) and here (Day 2), from Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh (2022).

- Regular lessons learned sessions following a disaster can help ensure relevance as well as capture evolving changes and trends, and the emergency preparedness actions needed. At the end of seasonal weather patterns, or a pause in the intensity of an emergency response, make time to reflect as a cluster, and enquire of affected populations’ perspective of the results and impact of the assistance they have received. See 5.11 on lessons learned.

In practical terms, the FSC Coordinator should: Contribute actively to the inter-agency level CP activities and/or develop a FSC CP (and ensure related activities). In addition to three core components (see above), this includes:

- Identifying early actions (see below) and triggers for the FSC.

- Developing a common response strategy for the FSC i.e. developing different food security response options including food assistance, agriculture (fisheries, livestock, crops and seeds) and other livelihood activities and modalities (see 5.6 on harmonisation).

- Identifying operational capacity and arrangements to ensure that food and other required inputs reach target populations in an emergency.

- Working with partners on preparatory measures (reviewing existing tools / assessment toolkits etc) to ensure food security related or inter-sectoral needs assessments are undertaken in a coherent, competent, systematic, and coordinated manner following an emergency. See 6.3.1 for more on assessment preparedness and early warning and monitoring systems.

- Having an inclusive approach and representative participation/consultation with affected and vulnerable groups during the response preparedness planning process.

- Ensuring that contingency planning and related activities (risk analysis, mitigation, and solutions/early action) are included by both the FSC team and partners in HNOs, SOPs, preparedness plans, etc.

- Ensuring the ICCG is informed of FSC preparedness activities to avoid duplication in efforts.

It is recommended to establish ad hoc TWGs, as relevant, to support the above CP related work.

See the IASC contingency plan template for overall suggested content and pp. 16-17 in gFSC Emergency Preparedness Planning Guidelines.

FSC Standard Operating Procedures

In support of the MPAs and APAs – and often a helpful tool in the CP process- the FSC can use a standard set of SOPs to guide the cluster in its initial emergency response. These SOPs detail the major steps to take during the emergency alert phase (the timeframe between an early warning trigger and the actual occurrence of a disaster) and/or, as appropriate and depending on the nature of the emergency, the immediate response and relief phase (from the first 24-72 hours and through the first few weeks from the onset of the emergency) - see template in the gFSC Guidelines (pp. 26-28 here) which can be customised as appropriate.

Early Action and Anticipatory Action

The Emergency Relief Coordinator, in 2021, flagged that “fifty percent of emergencies are foreseeable, and twenty percent are predictable” (see here). It is important for the FSC (and inter-agency) contingency planning to identify early actions, also known as anticipatory action (AA). Both FAO and WFP have contributed significantly to the work on this.

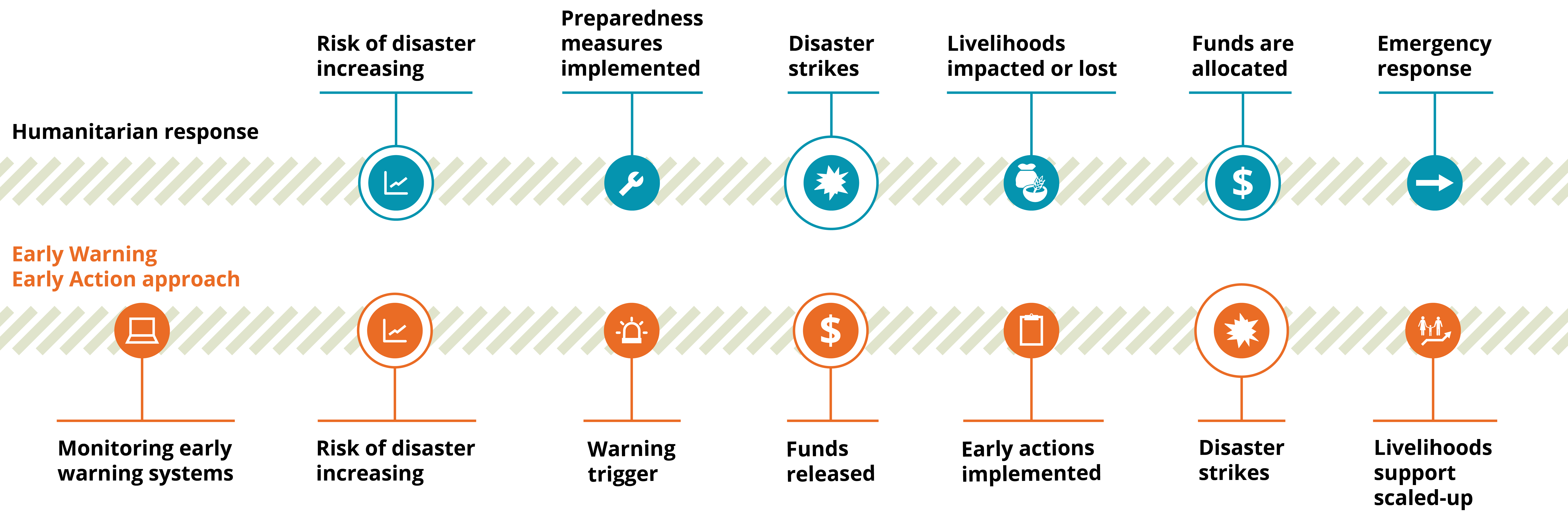

Early actions (or AA) are specific interventions or activities that clusters and organizations can implement in response to an early warning trigger, before a disaster has occurred (i.e. within the ‘anticipatory window’), in order to prevent and or mitigate the impact of the predicted event on lives and livelihoods. Acting early is generally cheaper than providing relief after a shock and this could therefore ease the pressure on limited global humanitarian funding and, in theory, could mean that more people can receive life- and livelihood-saving assistance. Anticipatory actions can be triggered once agreed risk-level thresholds are exceeded (based on agreed relevant early warning indicators).

A growing number of countries, where weather extremes and human-induced hazards pose a threat to lives, livelihoods and food security, have set up anticipatory action systems. A two-year pilot with CERF funds (see 8.4.3) allocated for anticipatory action relating to disasters/hazards was initiated in 2020 with Anticipatory Action frameworks developed in, for example Somalia, Bangladesh and Ethiopia. The current trend points towards a shift from piloting such frameworks to aiming to fully integrating these into humanitarian efforts.

This diagram illustrates what an early action approach might look like, where FSC partners act ahead of a typical humanitarian response in terms of timing of action and resourcing.

Examples of early action in a rapid onset emergency includes the distribution of cash to population who will be affected by floods. Cash distribution will take place between the early warning alert and the floods occurring. For slow onset emergencies, FSC partners might distribute drought-resistant seeds three months before the start of a lean season that is projected to be extremely dry.

Note: This section will be regularly updated in line with ongoing developments and FSC specific guidance to be developed in coming years.

The Coordinator is responsible for helping to ensure that the FSC is ready and able to provide a timely and effective response to imminent risks. He/she will actively contribute to and/or lead emergency preparedness (‘operational readiness’) activities: at inter-agency level through the ICCG (i.e. the ERP which includes risk monitoring, MPAs, APAs, joint contingency planning) and FSC specific processes (i.e. the FSC specific CP with all associated products as explained above). This includes the specific responsibilities outlined above.

Training and Capacity Strengthening Initiatives: In addition, the FSC Coordinator should also contribute to capacity strengthening initiatives for FSC partners, national authorities, and civil society to ensure a timely and appropriate response to an emergency situation. This includes:

- Identifying / prioritizing training needs in relation to assessments, monitoring, response planning, and the delivery of key food security services and assistance;

- Disseminating key selected technical guidance materials;

- Coordinating training initiatives with FSC partners and organising workshops on topics relevant to the local context, including joint exercises and tabletop simulations, priority cross-cutting issues and standards. See also 3.7 on capacity strengthening;

- Facilitating lessons learned from past activities and revising strategies accordingly.

Emergency Preparedness Working Group: The Coordinator may set up a dedicated Emergency Preparedness WG to help coordinate/facilitate the FSC preparedness response - see this example of such a WG TOR from Palestine. An ad hoc WG can be created prior to specific weather season (i.e. cyclone or flood season) in order to, for example, check the contingency stocks of partners and generally ensure to review the activities and core steps highlighted under the above “FSC Specific Contingency Planning” section in case updates are needed.

Guidance and Tools on Emergency Preparedness and Contingency Planning:

- The gFSC Emergency Preparedness Planning Guidelines (2015) are designed to assist FSC Coordinators set in place the necessary preparedness arrangements between emergency events at country level. This includes guidance on risk monitoring, MPAs, APAs, SOPs and contingency planning.

- For Inter-Agency guidance see: IASC Emergency Response Preparedness (ERP) Guidelines (IASC, 2015), the Interim Guidance on the Emergency Response Preparedness Approach to the COVID-19 Pandemic (IASC, 2020). See also the IASC ERP Contingency Plan Template (note that content from HumanitarianResponse.org will shift to ReliefWeb in 2023).

Other Resources:

- gFSC: See more resources on Preparedness and Contingency Planning on the FSC website here. The gFSC Preparedness and Resilience Working Group (PRWG) page includes further resources to guide country-level FSCs, including Lessons Learned on Early Warning, Early Action and Resilience. See also the FSC Guiding Questions on Preparedness and Resilience (2017) and gFSC Discussion Paper: Options to Address Preparedness and Resilience Building, (2016).

- For information on joint planning to improve synergy between humanitarian activities and resilience and peace efforts see 10.2.3.

- The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), is a leading provider of early warning and analysis on acute food insecurity around the world. See more on early warning and monitoring systems in 6.3.1.

- For more on Anticipatory Action and Early Action, see for example:

- Websites with relevant reports, tools and resources on anticipatory action: Anticipatory Action: A Commitment to Act Ahead of Crises (OCHA, 2021) and Anticipatory Action (OCHA). See also this Anticipatory Action Toolkit.

- See also the Anticipation Hub (see video), the Risk-informed Early Action Partnership (REAP), the Crisis Lookout Coalition, and the Anticipatory Action Task Force (IFRC, Start Network, FAO, WFP and OCHA, set up in 2018).

- Striking Before Disasters Do – Promoting phased Anticipatory Action for slow-onset hazards (Position paper, FAO, 2022). See also recent FAO publications on the effectiveness of anticipatory action in Bangladesh and Philippines and The evidence base on Anticipatory Action (WFP and ODI, 2020).

- Disaster Risk Reduction: For information on disaster risk reduction, another aspect of emergency preparedness, see for example pp. 177-186 in the Handbook for the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator (IASC, 2021). See also the UN’s Office for Disaster Risk Reduction including this checklist (UNDRR, 2021) developed to support the integration of disaster risk considerations in HRPs. UNDRR is currently working on a Words into Action (WiA) Guide on Multi-hazard Early Warning Systems – Placeholder, expected in 2023.