While governments have the primary responsibility for both humanitarian response and for having preparedness mechanisms in place, in disaster-prone countries, the RC/HC, through the HCT (or UNCT where IASC humanitarian coordination structures are not in place), can call on CLAs to operationalise the IASC Emergency Response Preparedness (ERP) approach in their respective clusters/sectors. This approach is intended to complement national preparedness efforts and guide the work of humanitarian organizations to respond if and when national capacity is not enough. The ERP aims to increase the speed, volume and effectiveness of assistance delivered in the first weeks of an emergency. It also aims to enhance predictability by establishing predefined roles, responsibilities, and coordination mechanisms.

The process is led by RC/HC and managed by the HCT, who provides the overarching framework to guide the collective action of all potential humanitarian responders, including clusters (sectors). The HCT will ensure coordination with existing national coordination structures when it is not feasible for the government to lead the process. The ICCG (with OCHA support) will support this process and ensure participation of cluster members, including local actors. Whenever possible, CLAs should coordinate closely with government counterparts. In refugee situations, UNHCR will lead the refugee preparedness and response in accordance with its responsibilities (see 4.2.2 on coordination in refugee crises).

Three Main Components of the ERP Approach

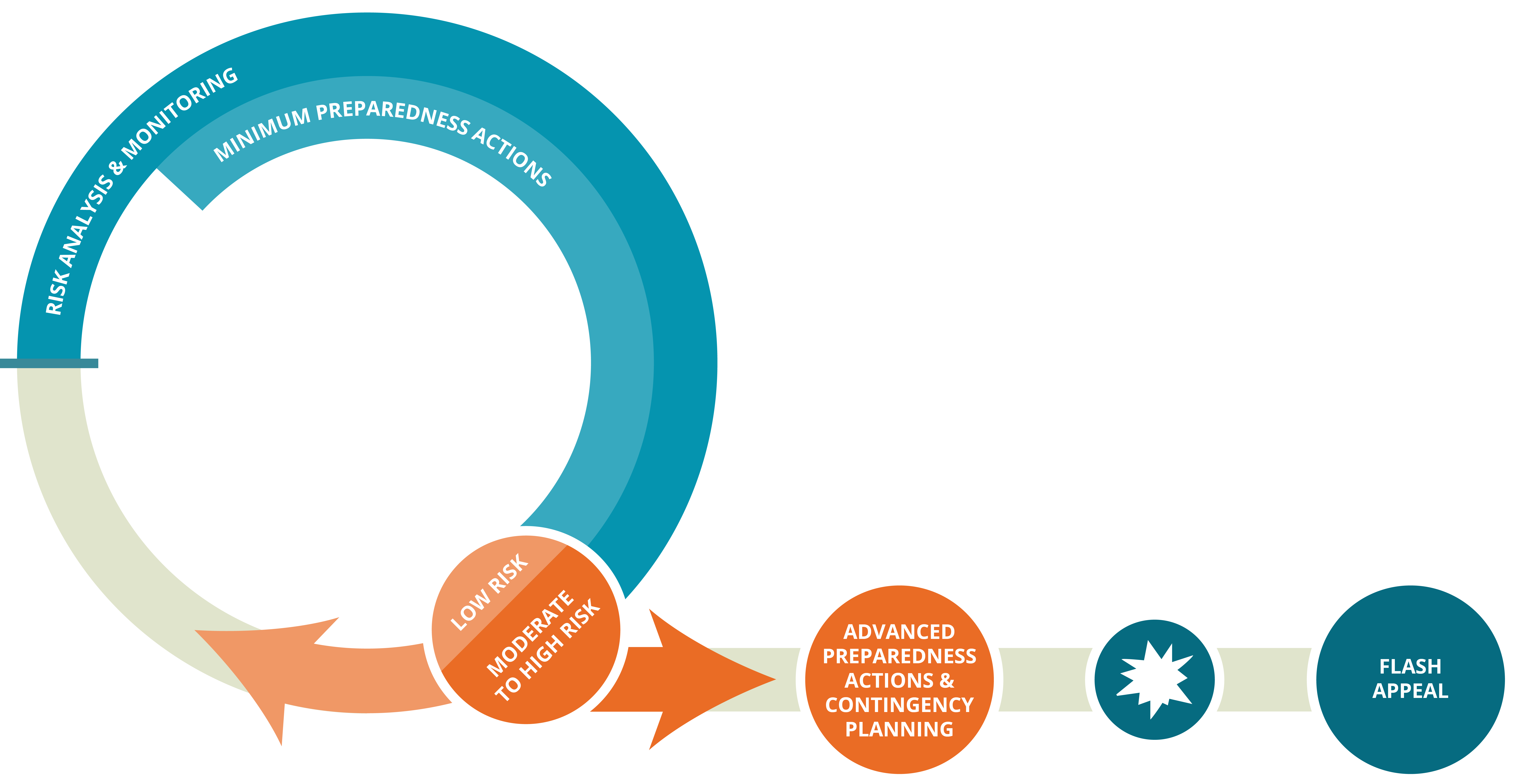

Through the HCT and the ICCG, the FSC takes active part in all three main components of the ERP (illustrated in this diagram, adapted from the IASC Emergency Response Preparedness (ERP) Guidelines (IASC, 2015), p. 8 (IASC, 2015):

① Risk Analysis and Monitoring:

It is fundamental to the entire ERP process to have a common understanding of the risks that may trigger a crisis. This requires risk analysis, which informs the planning as well as risk monitoring, which ensures that the process is responsive to emerging risks. Implementing this involves four steps and the FSC Coordinator should provide inputs, as requested by the HCT, usually through the ICCG:

- Hazard identification: The risk analysis process identifies the hazards that could trigger a crisis and ranks them by potential impact and likelihood.

- Risk ranking: The risk ranking determines whether thresholds are low, medium, or high. Development of a contingency plan is recommended when risk thresholds are determined to be medium or above.

- Defining thresholds: HCTs should agree on indicators for the risks identified and review them regularly.

- Risk monitoring: This provides early warning of emerging risks, which in turn allows for early action, such as tailoring the contingency plan and where possible, taking action that could mitigate the impact of the risk.

- Ensure that risk analysis and monitoring is undertaken regularly. Participate in analysing and addressing anticipated risks and represent FSC partners at inter-agency level (ICCG and HCT). Ensure that food security elements are fully integrated into risk assessments. This could involve organising risk analysis workshops with partners, including other clusters and the development of country specific joint risk analysis guidance. See details on risk analysis and risk monitoring, pp. 14-20 in the IASC ERP Guidelines and pp. 6-8 in the gFSC Emergency Preparedness Planning Guidelines.

- Disseminate (and act on) early warning alerts for coordination, prepositioning/contingency planning, and strategic response (see 5.8.2). This means that the Coordinator should share all relevant early warning alerts and initiate necessary actions – whilst being mindful of the government protocols (i.e. the FSC can only disseminate official messages, especially on weather alerts). Realtime monitoring of humanitarian situations should be translated into early action recommendations (see early actions below). See also 6.3.1 on early warning and monitoring systemsand the role of the Coordinator in repackaging early warning data and acting on such data.

② Minimum Preparedness Actions (MPA):

MPAs are a set of core preparedness actions that need to be undertaken by the HCT (through the ICCG and clusters) to achieve positive outcomes in the initial emergency response phase. The MPAs are not risk or scenario-specific and usually do not require significant additional resources to implement. They focus on practical actions to improve interagency response, accountability, and predictability and to promote more effective coordination between humanitarian actors.

MPAs focus on the following areas: monitoring risk and response, establishing coordination and information management systems, preparing for joint needs assessments, and establishing operational capacity (often referred to as operational preparedness) to deliver emergency assistance.

③ Advanced Preparedness Actions (APA) and Contingency Planning (CP):

Advanced Preparedness Actions: When an HCT, through risk analysis and monitoring, has identified a specific moderate or high risk (for example seasonal risks such as cyclones, floods or drought), APAs should be applied. These are designed to move the UNCT/HCT (and the relevant clusters) from ‘preparedness’ to ‘readiness’ to respond. Unlike MPAs, APAs are therefore risk specific. They build on the MPAs already in place and focus on the same areas but with strong focus on identifying elements that are essential for responding to a potential crisis (including resource requirements, linkages with national authority plans and contingency planning).

Contingency Planning: The second component (complementary to the APAs) when HCT has identified a moderate or high risk is inter-agency contingency planning (and where relevant, cluster specific), which sets out the initial response strategy and operational plan to meet needs during the immediate period following an emergency. The APA checklist includes essential preparedness actions that complement and support the contingency planning process.